Tropical Malady (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2004)

After only a few films, it’s obvious

that Thai filmmaker Apichatpong “Joe” Weerasethakul has no interest in the

conventions of narrative cinema. With Mysterious Object at Noon, a film

that seemed at first to be a harrowing documentary before it embarked on a

shifting, multi-narrator fictional tale, and Blissfully Yours, an

idyllic, erotic, yet mundane, outing that unfolded largely in real time, he’s

stunted audience expectation while conveying a semi-rural picture of Thailand

that’s unmistakably his own. Now, with Tropical Malady, Apichatpong

continues to grow as a filmmaker, creating this time a work of nearly

unparalleled ambition and remarkable control, despite what's perhaps his most confounding

narrative rug-pulling yet. Divided into two distinct, yet thematically linked

parts, Tropical Malady complexly tells the story of the emotional

development of a relationship between Keng, a solider in the Thai army, and

Tong, a farm boy that Keng meets during his duties. Its first half assumes the

mode of a relatively conventional gay romance but its second extends the themes

established there into a lyrical expansion of the film's prior concerns. With

this film, Apichatpong is working on so many levels that at first glance exact

attitude or meaning becomes difficult to pin down, since each explanation

seems to reduce other, somewhat valid readings. Such density is a blessing,

however, and a film that so blatantly challenges us yet has the goods to back up

such a test of an audience's ability is a rarity. It’s taken me four viewings to reach the

point where I felt I could adequately and succinctly describe its effect on me,

yet for all of the complexity of Malady’s defiantly modern mode of

storytelling, it hasn’t forgotten its roots.

After only a few films, it’s obvious

that Thai filmmaker Apichatpong “Joe” Weerasethakul has no interest in the

conventions of narrative cinema. With Mysterious Object at Noon, a film

that seemed at first to be a harrowing documentary before it embarked on a

shifting, multi-narrator fictional tale, and Blissfully Yours, an

idyllic, erotic, yet mundane, outing that unfolded largely in real time, he’s

stunted audience expectation while conveying a semi-rural picture of Thailand

that’s unmistakably his own. Now, with Tropical Malady, Apichatpong

continues to grow as a filmmaker, creating this time a work of nearly

unparalleled ambition and remarkable control, despite what's perhaps his most confounding

narrative rug-pulling yet. Divided into two distinct, yet thematically linked

parts, Tropical Malady complexly tells the story of the emotional

development of a relationship between Keng, a solider in the Thai army, and

Tong, a farm boy that Keng meets during his duties. Its first half assumes the

mode of a relatively conventional gay romance but its second extends the themes

established there into a lyrical expansion of the film's prior concerns. With

this film, Apichatpong is working on so many levels that at first glance exact

attitude or meaning becomes difficult to pin down, since each explanation

seems to reduce other, somewhat valid readings. Such density is a blessing,

however, and a film that so blatantly challenges us yet has the goods to back up

such a test of an audience's ability is a rarity. It’s taken me four viewings to reach the

point where I felt I could adequately and succinctly describe its effect on me,

yet for all of the complexity of Malady’s defiantly modern mode of

storytelling, it hasn’t forgotten its roots.

Circling around the moment when Eros

meets intimacy, where romance meets friendship, and where you stop thinking of

yourself as an individual and start thinking of yourself as part of a couple, Tropical

Malady is easier to follow in its first half, which introduces us to Keng

and Tong. As their friendship tentatively blossoms into love, this sequence

plays out as a series of magic moments, each conveyed with extraordinary

attention to environmental detail and emotional nuance. That’s not to say that

it’s an unbridled romance, though. Cropping up from time to time, there’s

the man who reminds Keng of his more frivolous romantic past, and just as

importantly there are small resistances that can be noted in Tong’s attitudes

and body language. The two men are clearly heading into a romantic

relationship, but Tong deflects both Keng’s physical advances and his

mother’s suggestion that Keng is falling for him. As their flirtation

advances, the boyish Tong adopts a playful manner in his interactions with Keng

that becomes an obvious defense mechanism.

Even when the two men fondle each other in a movie theater or proclaim

their affection, Tong is sure to leave the path to escape open by turning it

into a small joke. Throughout the

first half of the film, despite his obvious affection for Keng, he seems a

heartbeat away from writing off the more serious side of their relationship. As such, there’s a mild, noncommittal anxiety present even in the

film’s most idyllic scenes, and that unease only intensifies as the film moves

into its second half.

Circling around the moment when Eros

meets intimacy, where romance meets friendship, and where you stop thinking of

yourself as an individual and start thinking of yourself as part of a couple, Tropical

Malady is easier to follow in its first half, which introduces us to Keng

and Tong. As their friendship tentatively blossoms into love, this sequence

plays out as a series of magic moments, each conveyed with extraordinary

attention to environmental detail and emotional nuance. That’s not to say that

it’s an unbridled romance, though. Cropping up from time to time, there’s

the man who reminds Keng of his more frivolous romantic past, and just as

importantly there are small resistances that can be noted in Tong’s attitudes

and body language. The two men are clearly heading into a romantic

relationship, but Tong deflects both Keng’s physical advances and his

mother’s suggestion that Keng is falling for him. As their flirtation

advances, the boyish Tong adopts a playful manner in his interactions with Keng

that becomes an obvious defense mechanism.

Even when the two men fondle each other in a movie theater or proclaim

their affection, Tong is sure to leave the path to escape open by turning it

into a small joke. Throughout the

first half of the film, despite his obvious affection for Keng, he seems a

heartbeat away from writing off the more serious side of their relationship. As such, there’s a mild, noncommittal anxiety present even in the

film’s most idyllic scenes, and that unease only intensifies as the film moves

into its second half.

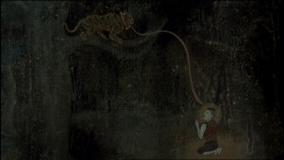

The first half of Tropical Malady ends

as Keng leaves for the country, his furlough expired, with Tong and Keng’s

relationship at a point where it’s been mutually acknowledged but not yet

consummated. The latter half, dubbed A Spirit’s Path in the movie’s

second title sequence, marks a distinct stylistic break from the first, adopting

much darker imagery and a soundtrack that remains largely wordless. This equally

remarkable passage shows Keng on a highly sexualized chase after the tiger

spirit (embodied by Tong) that’s been terrorizing the village that Keng has been

assigned to protect. This sequence feels like a dream or a fantasy that his character’s

had after the events in the first half of the film, yet it’s so intensely

realized and so undeniably relevant that to write it off as such is to do the

film a great disservice. It’s best, I think, to experience the two parts of

the film as one continuous story, with the first half documenting country-boy

Tong’s slow acceptance of his homosexuality and indoctrination to the city and

the latter half poetically detailing Keng’s exotic confrontation of the ideal

of true love (as opposed to his past empty carnality) and the way that merging

with another, body and soul, threatens to erase his own identity. Besides, there

are strong hints, such as the emergence of the naked man in the film’s first

scene or the hum of the motorcycle in its final shot that encourage such a

unified reading.

The first half of Tropical Malady ends

as Keng leaves for the country, his furlough expired, with Tong and Keng’s

relationship at a point where it’s been mutually acknowledged but not yet

consummated. The latter half, dubbed A Spirit’s Path in the movie’s

second title sequence, marks a distinct stylistic break from the first, adopting

much darker imagery and a soundtrack that remains largely wordless. This equally

remarkable passage shows Keng on a highly sexualized chase after the tiger

spirit (embodied by Tong) that’s been terrorizing the village that Keng has been

assigned to protect. This sequence feels like a dream or a fantasy that his character’s

had after the events in the first half of the film, yet it’s so intensely

realized and so undeniably relevant that to write it off as such is to do the

film a great disservice. It’s best, I think, to experience the two parts of

the film as one continuous story, with the first half documenting country-boy

Tong’s slow acceptance of his homosexuality and indoctrination to the city and

the latter half poetically detailing Keng’s exotic confrontation of the ideal

of true love (as opposed to his past empty carnality) and the way that merging

with another, body and soul, threatens to erase his own identity. Besides, there

are strong hints, such as the emergence of the naked man in the film’s first

scene or the hum of the motorcycle in its final shot that encourage such a

unified reading.

Symbolically, the two men represent what

I’ll describe in simple terms as “modernity” and “myth”. Throughout

the film, we’re presented images in which these two seemingly diametric

notions collide, yet somehow rest in unity. Some of these collisions, like the

Christmas lights strewn across a religious shrine or the casual mention of

“Who Wants to Be a Millionaire” in the middle of a retelling of an old folk

tale, are humorous, but consistently they’re presented in a way that feels

less like an either/or dichotomy than a prescient glance toward the ultimate

consummation of these two beings. The men themselves undergo transformations

that smear the notions of their identity that existed at the film’s start.

Keng’s devolution in the second half is made incredibly evident. Physically,

his uniform is stripped away layer by layer as he continues his pursuit,

reducing him to the point where he begins to crawl on all fours. Spiritually, he

undergoes an even more radical shift toward the mythic, and finds himself

talking to animals and seeing ghosts. Since Tong’s growth in the first half of

the film is grounded in his acceptance of reality, it is necessarily more

mundane, yet it’s just as astutely detailed. We watch as this farm boy learns

to drive and heads to the city to search for a job, and through his gradual

acceptance of his sexuality (no out-of-the-closet melodrama here!) we can

observe his emotional growth. As much as the film is about Tong and Keng’s

love, it’s about the attempt to harmonize their two vastly different

lifestyles, each of which is present alongside the other in modern Thai culture.

Symbolically, the two men represent what

I’ll describe in simple terms as “modernity” and “myth”. Throughout

the film, we’re presented images in which these two seemingly diametric

notions collide, yet somehow rest in unity. Some of these collisions, like the

Christmas lights strewn across a religious shrine or the casual mention of

“Who Wants to Be a Millionaire” in the middle of a retelling of an old folk

tale, are humorous, but consistently they’re presented in a way that feels

less like an either/or dichotomy than a prescient glance toward the ultimate

consummation of these two beings. The men themselves undergo transformations

that smear the notions of their identity that existed at the film’s start.

Keng’s devolution in the second half is made incredibly evident. Physically,

his uniform is stripped away layer by layer as he continues his pursuit,

reducing him to the point where he begins to crawl on all fours. Spiritually, he

undergoes an even more radical shift toward the mythic, and finds himself

talking to animals and seeing ghosts. Since Tong’s growth in the first half of

the film is grounded in his acceptance of reality, it is necessarily more

mundane, yet it’s just as astutely detailed. We watch as this farm boy learns

to drive and heads to the city to search for a job, and through his gradual

acceptance of his sexuality (no out-of-the-closet melodrama here!) we can

observe his emotional growth. As much as the film is about Tong and Keng’s

love, it’s about the attempt to harmonize their two vastly different

lifestyles, each of which is present alongside the other in modern Thai culture.

Yet it’s more than just that. After

all, Keng’s entry onto a mystic, metaphysical plane in which he can truly love

taken with Tong’s owning up to the physical reality of his identity

overpoweringly demonstrates the need for both carnality and companionship to

achieve a true union. “I give you my spirit, my flesh and my memories. Every

drop of my blood sings our song. A song of happiness. There… do you hear

it?”, the final words of the film, are anything but a letdown after an

unbearable buildup. The rush of the mythic closing moments of Tropical Malady,

in which its myriad themes coalesce into the orgasmic consummation of their

infinite promise, is one of the most transcendent expressions of love in all of

cinema. For a brief, exalted moment, Tropical Malady achieves an ideal.

Through his unconventional means, Apichatpong poetically expresses the

transformative quality of love, realizing a kind of intense profundity that

simply could not be reached in any other medium.

Yet it’s more than just that. After

all, Keng’s entry onto a mystic, metaphysical plane in which he can truly love

taken with Tong’s owning up to the physical reality of his identity

overpoweringly demonstrates the need for both carnality and companionship to

achieve a true union. “I give you my spirit, my flesh and my memories. Every

drop of my blood sings our song. A song of happiness. There… do you hear

it?”, the final words of the film, are anything but a letdown after an

unbearable buildup. The rush of the mythic closing moments of Tropical Malady,

in which its myriad themes coalesce into the orgasmic consummation of their

infinite promise, is one of the most transcendent expressions of love in all of

cinema. For a brief, exalted moment, Tropical Malady achieves an ideal.

Through his unconventional means, Apichatpong poetically expresses the

transformative quality of love, realizing a kind of intense profundity that

simply could not be reached in any other medium.

94

08.03.05

Jeremy Heilman